; then, in classical calculus, we can easily integrate it from

; then, in classical calculus, we can easily integrate it from  to

to

.

.

As you might have already guessed, we deal with discrete functions rather

than continuous ones in discrete calculus. A rather peculiar idea comes to

mind here: integrating such a function. Let us consider a simple function

; then, in classical calculus, we can easily integrate it from

; then, in classical calculus, we can easily integrate it from  to

to

.

.

| (1) |

However, what if we limit the function and accept only integer  ? Then, the

integration becomes a summation, which is more complicated.

? Then, the

integration becomes a summation, which is more complicated.

| (2) |

While some might find the latter simpler to understand, when we consider a more

complicated equation, it becomes way harder than anticipated. Consider the function

.

.

| (3) |

| (4) |

The equations look similar. However, the discrete version needs to adjust for all the non-integer values, which makes the equation more complicated. Ironically, it is simpler to calculate an infinite sum of infinitely small segments of a function than to sum a discrete number of values.

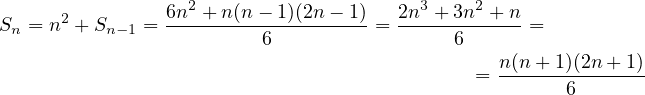

Sometimes, it is simpler to prove that a given equation works using induction than to find it. Consider, for example, the following equation.

| (5) |

It is quite simple to prove using induction. Let  be defined as the sum of the first

be defined as the sum of the first

natural numbers; then we can say the following.

natural numbers; then we can say the following.

| (6) |

With a similar method, it is simple to prove that,

| (7) |

Again, let  be the sum of the first

be the sum of the first  squares, then we can use induction,

assuming

squares, then we can use induction,

assuming  is bound by the equation above.

is bound by the equation above.

| (8) |

Just like in classical calculus, one must first understand the concept of a derivative before understanding integration. In classical calculus, one would define a derivative in the following way.

| (9) |

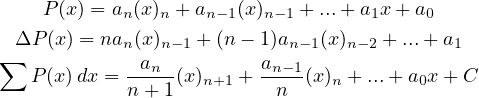

However, in discrete calculus, the smallest step one can make is  . Thus, a

discrete version of a derivative will look as follows.

. Thus, a

discrete version of a derivative will look as follows.

| (10) |

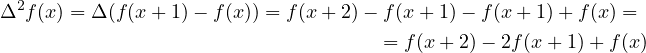

Usually, instead of saying discrete derivative, it is called the forward difference operator. Consider that; what about higher-order derivates? Then, notice that a second-order derivative would look as follows.

| (11) |

-th

order discrete derivative? As we will come to see, a formula does indeed

exist.

-th

order discrete derivative? As we will come to see, a formula does indeed

exist.

| (12) |

It is quite simple to see if we employ induction. Obviously, the statement is true for

. Let this serve as the base of the induction; now, assume the statement

is true for

. Let this serve as the base of the induction; now, assume the statement

is true for  , then one can prove that it works for

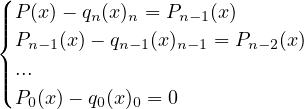

, then one can prove that it works for  as follows.

as follows.

![[ ]

n+1 n n∑ n-i(n )

Δ f(x) = Δ (Δ f (x)) = (- 1) i f(x+ 1 +i) -

[ ( ) ] i=0 ( ) ( )

∑n n-i n n n n∑ n-i+1 n

(- 1) i f(x + i) = - (- 1) 0 f(x)+ (- 1) i- 1 f(x+i )-

i=0 n ( ) i=1 ( )

∑ (- 1)n-i n f (x + i) +(- 1)0 n f(x +n + 1)

i=1 i n](discrete_calculus27x.png) | (13) |

, and get the following.

, and get the following. ![[ ]

(n ) ∑n (( n ) (n ))

...= - (- 1)n 0 f(x)+ (- 1)n+1-i i- 1 + i f(x +i) +

i=1

0(n) n+∑1 n+1-i(n)

(- 1) n f (x + n+ 1) = (- 1) i f(x+ i)

i=0](discrete_calculus29x.png) | (14) |

.

.

Seeing the analog of  in Discrete Calculus is interesting. Does there exist

such a constant

in Discrete Calculus is interesting. Does there exist

such a constant  , such that

, such that  ? As it turns out, there does,

2.

? As it turns out, there does,

2.

| (15) |

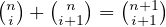

Many properties of classical calculus about derivatives, such as the Product/Quotient Rule, have analogs in discrete calculus. First, the obvious ones,

| (16) (17) |

| (18) |

The understanding is the same as that of classical calculus; we only got an extra term because terms are not infinitely small, as in classical calculus. Similarly, we have the Discrete Quotient Rule.

| (19) |

And again, this can be proven the exact same way it is proven in classical calculus, with only some minor changes.

Just as in normal calculus, such a thing as a discrete antiderivative exists. As in classical calculus, it is defined similarly.

| (20) |

Just as in classical calculus, it is tightly related to discrete integrals through the Fundamental Theorem of Discrete Calculus.

| (21) |

This can be proven in the exact same way the fundamental theorem of calculus is proven; I will leave this as an exercise for the reader.

In classical calculus, there is a very simple formula for calculating an antiderivative of a polynomial, as follows.

| (22) |

It would be useful to compute the discrete antiderivatives for polynomials as well.

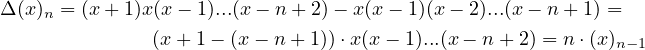

However, first, let us introduce some useful terminology. A falling factorial of  is

called the following.

is

called the following.

| (23) |

Sometimes, it might be called the  -th Pochhammer Polynomial. This function is

wonderful because it satisfies the following requirements.

-th Pochhammer Polynomial. This function is

wonderful because it satisfies the following requirements.

| (24) |

This can be seen through some trivial calculations.

|

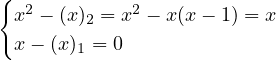

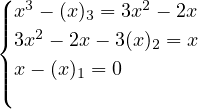

| (25) (26) (27) |

Find the dominant coefficient  of the polynomial

of the polynomial  .

.

Subtract from  the value

the value  , where

, where  is the degree of

is the degree of  .

.

Go to step one with the updated polynomial  .

.

In the end, one will get the following system of equations.

. For example,

convert

. For example,

convert  into the falling factorial polynomial form.

into the falling factorial polynomial form.

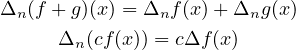

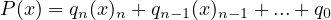

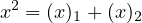

. As an example, this knowledge is already

enough to compute the sum of the first cubes

. As an example, this knowledge is already

enough to compute the sum of the first cubes  . One must first change the

expression into the falling factorial polynomial form from the equation (25).

. One must first change the

expression into the falling factorial polynomial form from the equation (25).

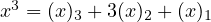

. From here, all that is left is to

integrate the expression.

. From here, all that is left is to

integrate the expression. ![∑n 3 [∑ 3 ]n+1 [∑ ( ) ]n+1

x = x dx 1 = (x)3 + 3(x)2 + (x)1 dx

x[=1 ] 1

(x)4- (x)2 n+1 (n+-1)n(n--1)(n---2)

= 4 + (x)3+ 2 +C 1 = 4 + (n+1 )n(n- 1)(n- 2)

( )2

+ (n-+-1)n= n(n-+1)-

2 2](discrete_calculus62x.png) | (28) |

| (29) |

With the same technique, discrete integrals of any polynomial can be found, even more than we originally hoped.

Generally speaking, the topic of discrete calculus has a lot of connections with stirring numbers; for example, the following holds true:

| (30) |

This can be used to prove various identities with falling factorials. Specifically, this relation shows us that instead of the tedious method described earlier for expressing a polynomial using a Pochhammer polynomial, it is important to note that in practice if one does not have access to machine calculations, the method described before is better. I will not explain this in this article; I will leave this for another time.

I hope that you have found the given material interesting and useful. Discrete Calculus is quite an exotic and fascinating topic in mathematics.