§

Introduction

Ramsey theory is a significant branch of mathematics; consequently, we will only look at Ramsey theorem and Ramsey numbers in this article. To start everything off, let us consider this quite simple problem.

Consider a complete graph of six nodes with the edges colored into two colors, red and blue, to prove that there will always exist either a red triangle or a blue triangle.

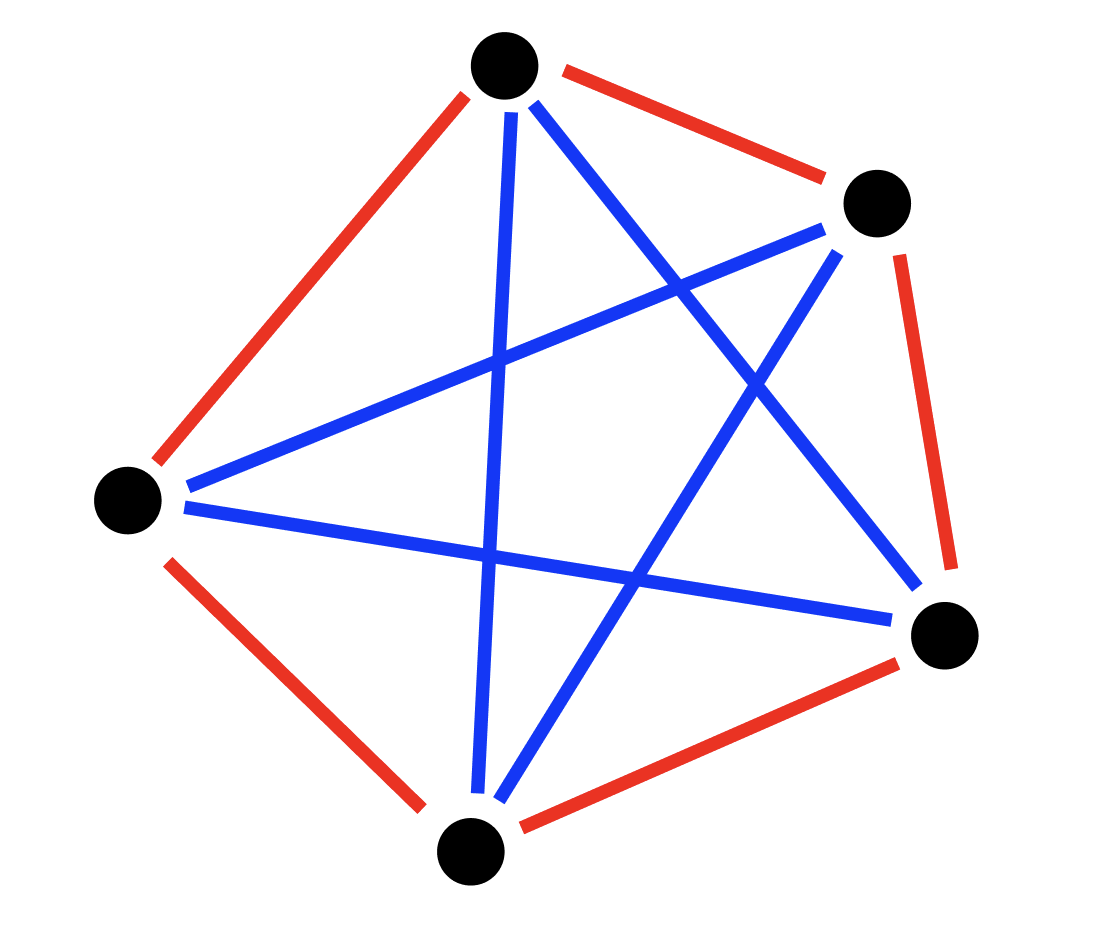

Consider one of the nodes A; it has five connections, meaning at least 3 are the same color; let it be blue. Now consider the three nodes these edges go to. If two of the three are connected with a blue edge, then by selecting those and A, we have found a blue triangle; by selecting those three nodes, we have discovered a red triangle. Notice that this statement is not valid for five nodes. Here is a counterexample.

Meaning summarizing everything we get that for any complete graph with more than 5 nodes colored into red and blue there will always exist either a blue triangle or a red one. Now let us make the problem more general, instead of looking for triangles we will be searching for complete subgraphs on k vertices. Then let us define a function

\(R(r, s)\) represents the minimum n such that for any complete graph on n nodes which is colored into two colors such that there will either exist a complete blue subgraph with r nodes, or a complete red subgraph with s nodes.

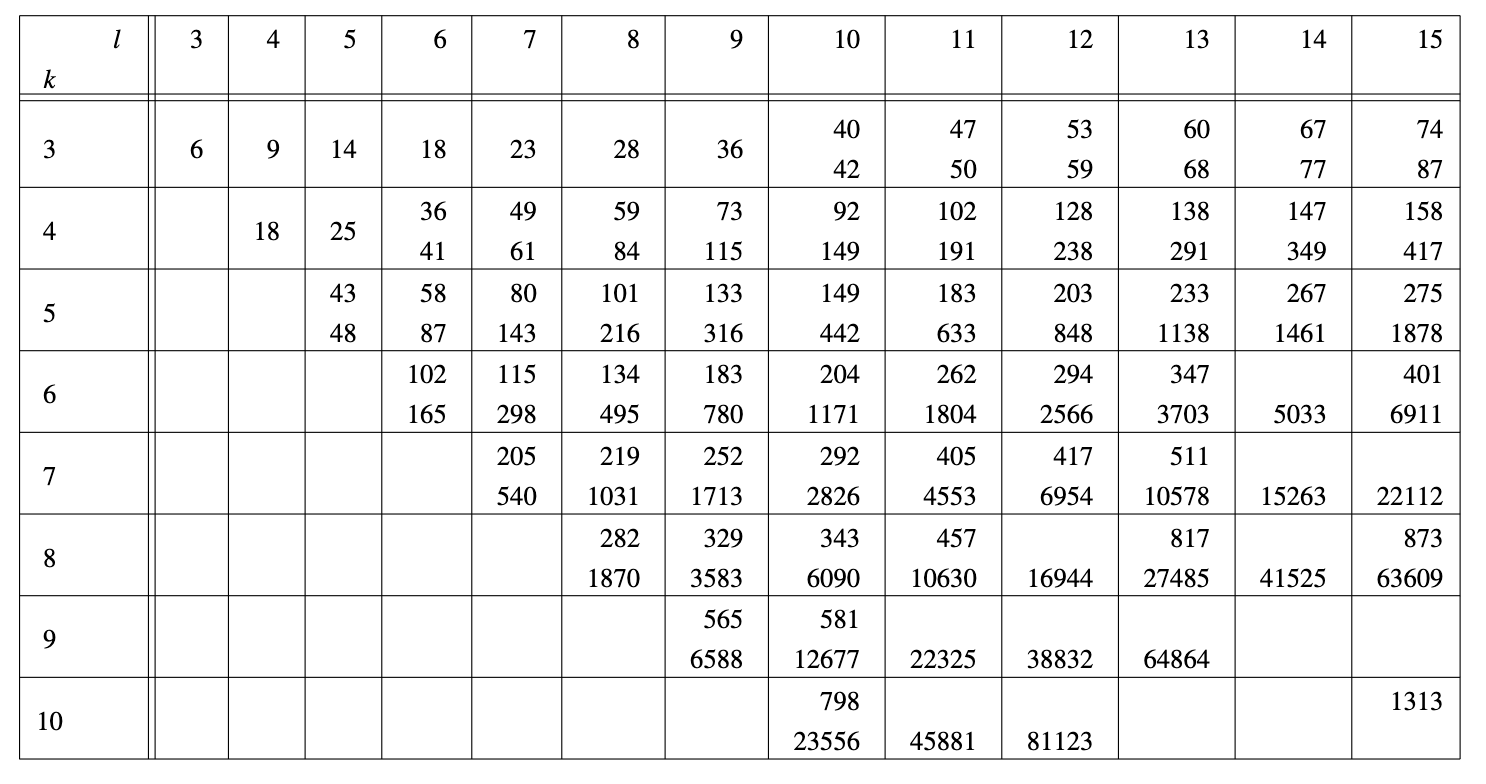

Then we can write down the previous statement as \(R(3, 3) = 6\). (Note that formaly this function can take more than two arguments, representing colorings into more than two colors, however in this article this will not be considered). Finding the value of \(R(4, 4)\) gets a bit harder but with a similar logic we can find that \(R(4, 4) = 18\). But starting from \(R(5, 5)\) humanity does not know the exact value of this function. Here is a table of the known Ramsey numbers. [1]

§

Finding a Lower Bound using Probability

The main idea is to prove that there is some positive probability that a solution exists. Then this means there exists a example where the needed outcome is achieved. Using this idea we will prove the following statement.

$$\forall k \geq 3: R(k, k) > \lfloor 2^{k/2} \rfloor$$Let us color a graph. \(G = K_n\) into two colors randomly. Let us also pick a random subgraph. \(R \in G\) and let \(|V(R)| = k\), then let \(A_R\) be the event that \(R\) is monochromatic. Then

$$\mathbb{P}(A_R) = 2 \cdot \frac{1}{2^{k \choose 2}} = 2^{1 - {k \choose 2}}$$Summing over all possible events \(A_R\) provides an upper bound on the probability that \(G\) contains a monochromatic induced subgraph on \(k\) vertices. And we get

$$\Sigma_{R \subset G, \ |R| = k} \mathbb{P}(A_R) = \binom{n}{k} 2^{1 - \binom{k}{2}}$$All that is left to show that this is less than one is to recall that. \(\binom{n}{k} \leq \frac{n^k}{k!}\) leading to us rewriting the equation into the following form.

$$\binom{n}{k} 2^{1 - \binom{k}{2}} < \frac{n^k}{k!} \cdot 2^{1 - k^2/2+k/2} = \frac{2^{1 + k/2}}{k!} \cdot \frac{n^k}{2^{k^2/2}}$$Now, let us plug in the original value for \(n = \left \lfloor 2^{k / 2} \right \rfloor\) and then we get

$$\frac{2^{1 + k/2}}{k!} \cdot \frac{2^{k^2/2}}{2^{k^2/2}} = \frac{2^{1 + k/2}}{k!} < 1$$This proves the original statement. [2]

§

Analysing Graph Components of Maximum counterexample to R(5, 5)

This section aims to analyse the components of the maximum counterexample to \(R(5, 5)\). First, let G be a graph with the maximum number of nodes so there is no \(K_5\) and no \(K_5\) in the complement of G. Then, it is trivial to see that

$$comp(G) < 5$$It is known that \(42 \leq |G| \leq 47\). This means if \(comp(G) = 4\), we would have a component with the size \( \left \lceil{\frac{n}{4}}\right \rceil \geq 11\), and because there is no way of picking 5 nodes which are not connected, we conclude all 4 components must be complete, meaning G contains \(K_{11}\) which contains \(K_5\), contradiction. This argument allows us to improve the initial statement.

$$comp(G) < 4$$Two of the three components must be complete if \(comp(G) = 3\). In such cases, there should be a component with \( \left \lceil{\frac{n}{3}}\right \rceil \geq 14\) nodes. If this component is one of the complete ones, we have found \(K_5\), so let us assume this component is the one that is not complete. Then, the other two components can't be greater than 4 because else we would have found a \(K_5\), meaning that the size of the selected component C is at least \(42 - 4 \cdot 2 = 34\) nodes. Zarankiewicz's lemma tells us there exists a node with a degree at most \( \left \lfloor{\frac{k-2}{k-1} \cdot n}\right \rfloor \leq 25\), indicating that there exists a node which isn't connected to the other 8 nodes in the same component. However, if any of the 8 nodes were not connected, we could select 2 from the complete components, the Zarankiewicz node, and the two nodes not connected from the 8 nodes. We would have found a \(K_5\) in the complement of G, meaning the 8 nodes create a complete graph \(K_8\), meaning they contain a \(K_5\), contradiction. Now, we bring the upper bound of the number of components down to two.

$$comp(G) < 3$$We can break this limit even further by noticing if we have two components. There are two options: one is complete, the other is not, or both are incomplete. If only one is complete, the other component will have at least 38 nodes, even more than the situation discussed for the 3 components. This means that the only option worth looking at is if both still need to be completed, but then at least one of them contains at least 21 nodes. There is a Zarankiewicz's node with at most \( \left \lfloor{\frac{k-2}{k-1} \cdot n}\right \rfloor \leq 15\) connections, meaning it is not connected with another 5 nodes applying the same argument as in the previous situation we conclude or there is a \(K_5\) in one of the components or there are three nodes in one component which are not connected adding another two from the other not complete component we again find a \(K_5\) in the complement of G.

This means \(G\) is connected. But by how much does this reduce the search space? Sadly not by much, since almost all graphs are connected meaning the probability that the graph is connected goes to 1 as the size of the graph goes to infinity.

§

References

[1] Radziszowski, S. (2011). Small ramsey numbers. The electronic journal of combinatorics, 1000, DS1-Aug.

[2] Balachandran, N. (2011). The Probabilistic Method in Combinatorics. Lectures by Niranjan Balachandran, Caltech.

§

Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramsey%27s_theorem